Station 56, County Budgets, and the Dangerous Myth of “Running Government Like a Business”

When the Tuolumne County Board of Supervisors voted to defund CAL FIRE Station 56, the reaction across the community was immediate and emotional. For many residents, the decision felt unnecessary and risky, especially in a county where wildfire is not an abstract threat but a lived reality. It also felt disconnected from common sense, as though the decision had been driven more by spreadsheets than by the real-world consequences of reduced fire protection.

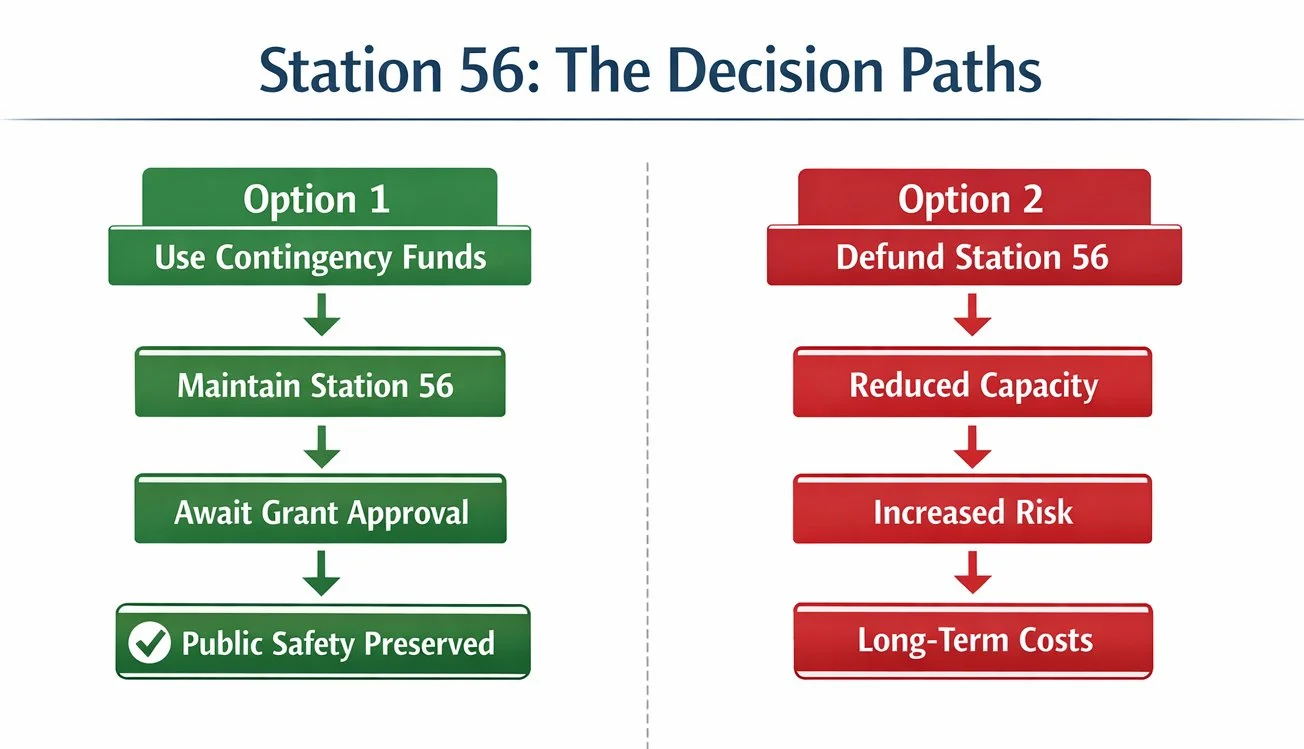

What most people did not see was the broader financial context. Tuolumne County maintains contingency funds specifically intended to address unexpected costs and temporary gaps in funding.

At the same time, there was a strong likelihood that state or federal grant funding would be approved later in the year, potentially offsetting the cost of maintaining Station 56. The financial gap cited in the debate was not insignificant, but it was not a crisis-level shortfall either. There were options available that did not require defunding a fire station.

That raises an important question. If Station 56 did not have to be cut, why was it?

The answer points to something larger than a single budget decision. It reveals how county finances are often misunderstood and why the instinct to run government like a business can lead to decisions that appear fiscally responsible on paper but are deeply risky in practice.

The Story Being Told About Station 56

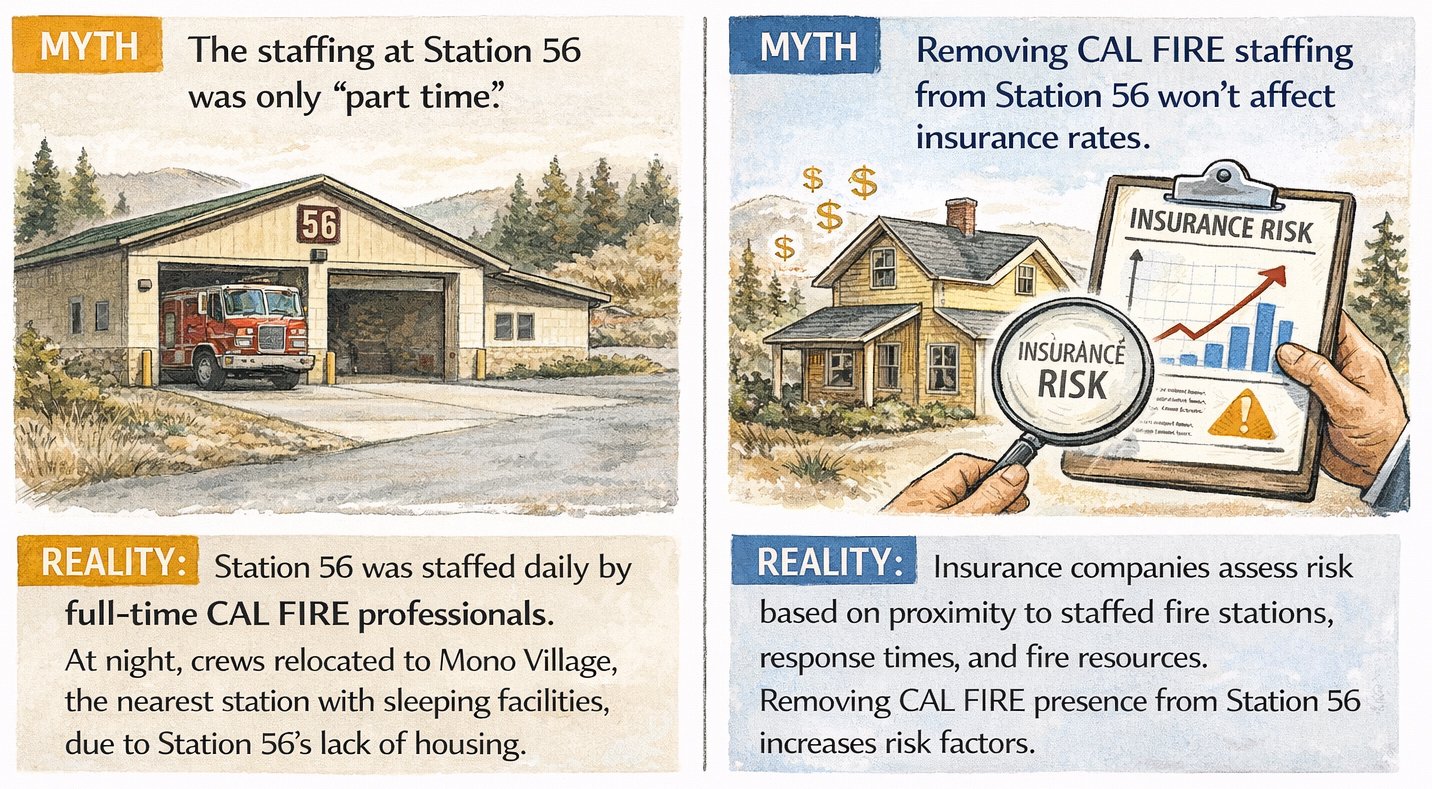

In the aftermath of the decision, two claims have circulated widely. One is that removing CAL FIRE staffing and an engine from Station 56 will not affect insurance rates in Tuolumne County. The other is that the staffing at Station 56 was only “part time.” Both claims deserve closer examination.

The firefighters assigned to Station 56 were not temporary or marginal personnel. They were full CAL FIRE professionals.

The fact that they did not sleep overnight at Station 56 was not a reflection of their status but of the station’s facilities. Station 56 lacked adequate sleeping accommodations, so crews relocated overnight to the Mono Village station, where proper infrastructure existed. During the day, Station 56 provided coverage in a high-risk area; at night, crews were staged at a nearby station that could support them. This arrangement was not “part time” in any meaningful sense. It was a logistical solution to a facilities constraint in a rural county.

Describing Station 56 as a part-time operation creates the impression that it was optional or peripheral. In reality, it was part of a broader coverage strategy in a county where response times and proximity matter. The difference between a staffed station and an unstaffed one is not theoretical. It affects how quickly help arrives when it is needed most.

The claim that defunding Station 56 will not affect insurance rates is even more difficult to reconcile with how insurance companies actually operate.

Insurers do not base their risk assessments on political assurances or optimistic interpretations of policy decisions. They rely on data: the distance to the nearest staffed station, the number of available engines, the expected response times, and the level of professional wildfire suppression capacity in the area. Removing staffed CAL FIRE presence and an engine from Station 56 changes those variables. When risk changes, insurance pricing eventually follows.

The impact may not be immediate, and it may not be uniform across the county, but it is unrealistic to assume that reducing fire protection capacity in a high-risk wildfire region will have no effect on insurance costs. Insurance companies operate on long-term risk models, not short-term messaging. When residents are told that defunding Station 56 will have no impact on insurance, they are being offered reassurance without evidence. That may be comforting, but it is not the same as being accurate.

What the Budget Actually Allowed

Counties maintain contingency funds precisely because not every expense fits neatly into a fiscal calendar. Wildfires, delayed funding, infrastructure failures, and economic fluctuations do not wait for budget cycles. Contingency funds exist to give governments the flexibility to respond to uncertainty without immediately dismantling essential services.

In Tuolumne County’s case, those funds could have been used to bridge the gap while awaiting confirmation of grant funding. This would not have required reckless spending or a permanent commitment to unsustainable costs. It would have been a temporary measure designed to preserve critical infrastructure during a period of uncertainty.

In other words, defunding Station 56 was not an unavoidable outcome. It was a choice shaped by priorities and risk tolerance. That distinction matters because it reframes the decision not as an act of fiscal necessity but as a reflection of how the county evaluates tradeoffs between financial caution and public safety.

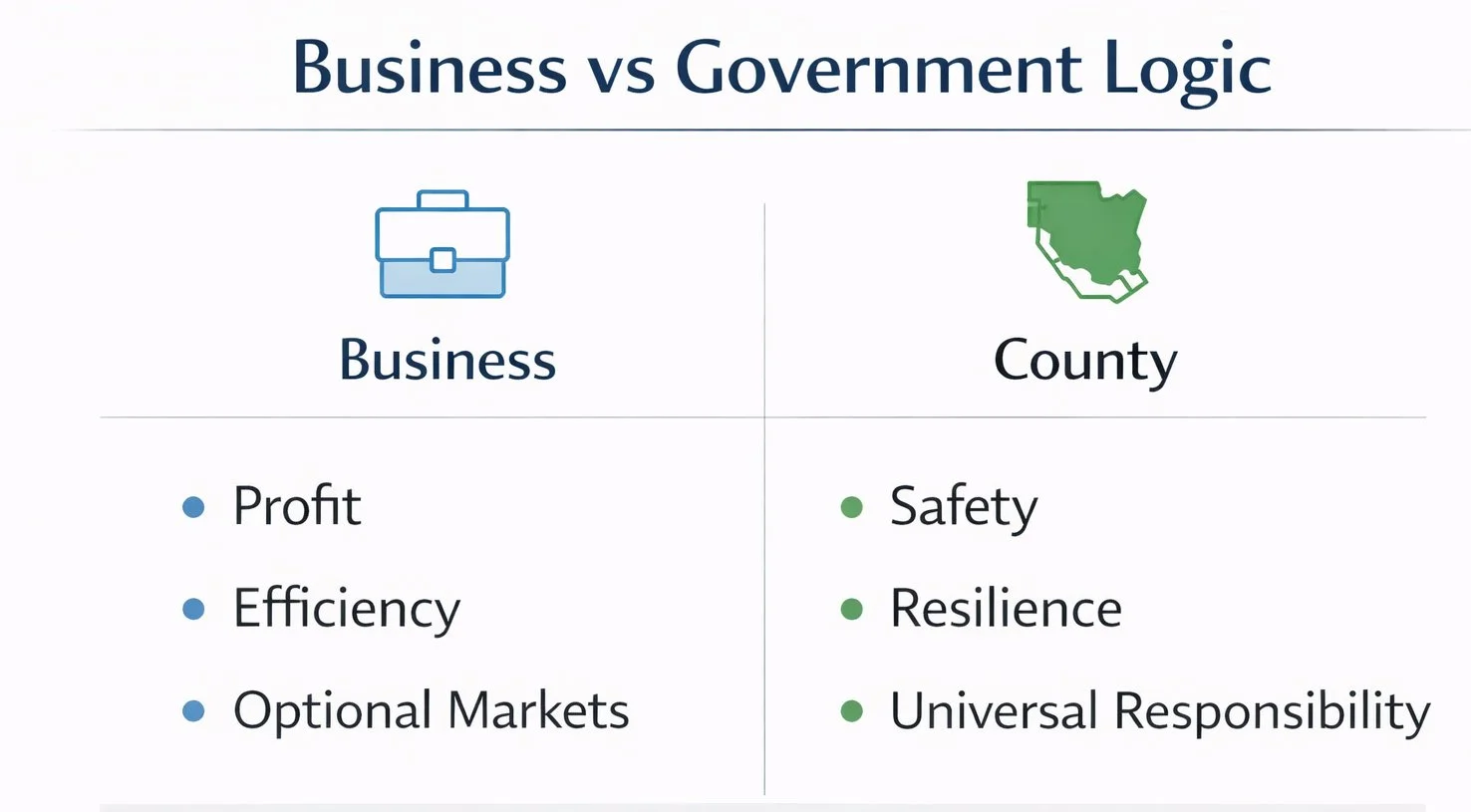

The Limits of Business Logic

The impulse to run government like a business is understandable. Businesses respond to uncertainty by cutting costs, minimizing risk, and protecting their bottom line. In the private sector, closing an underperforming branch or reducing overhead can be a rational and even necessary decision.

But a county is not a business. Its purpose is not to maximize profit but to provide essential services and protect public welfare. A business can choose to abandon unprofitable markets; a county cannot responsibly abandon communities exposed to real and growing risks. A business optimizes for efficiency; a county must optimize for resilience.

When business logic is applied uncritically to public safety, it can produce decisions that look prudent in spreadsheets but carry serious consequences in the real world.

Fire protection is not a discretionary program that can be trimmed without repercussions. It is foundational infrastructure, comparable to roads, water systems, and emergency medical services. Reducing that infrastructure may improve short-term financial metrics, but it increases long-term vulnerability.

The Broader Reality of County Budgets

To see the full presentation click HERE

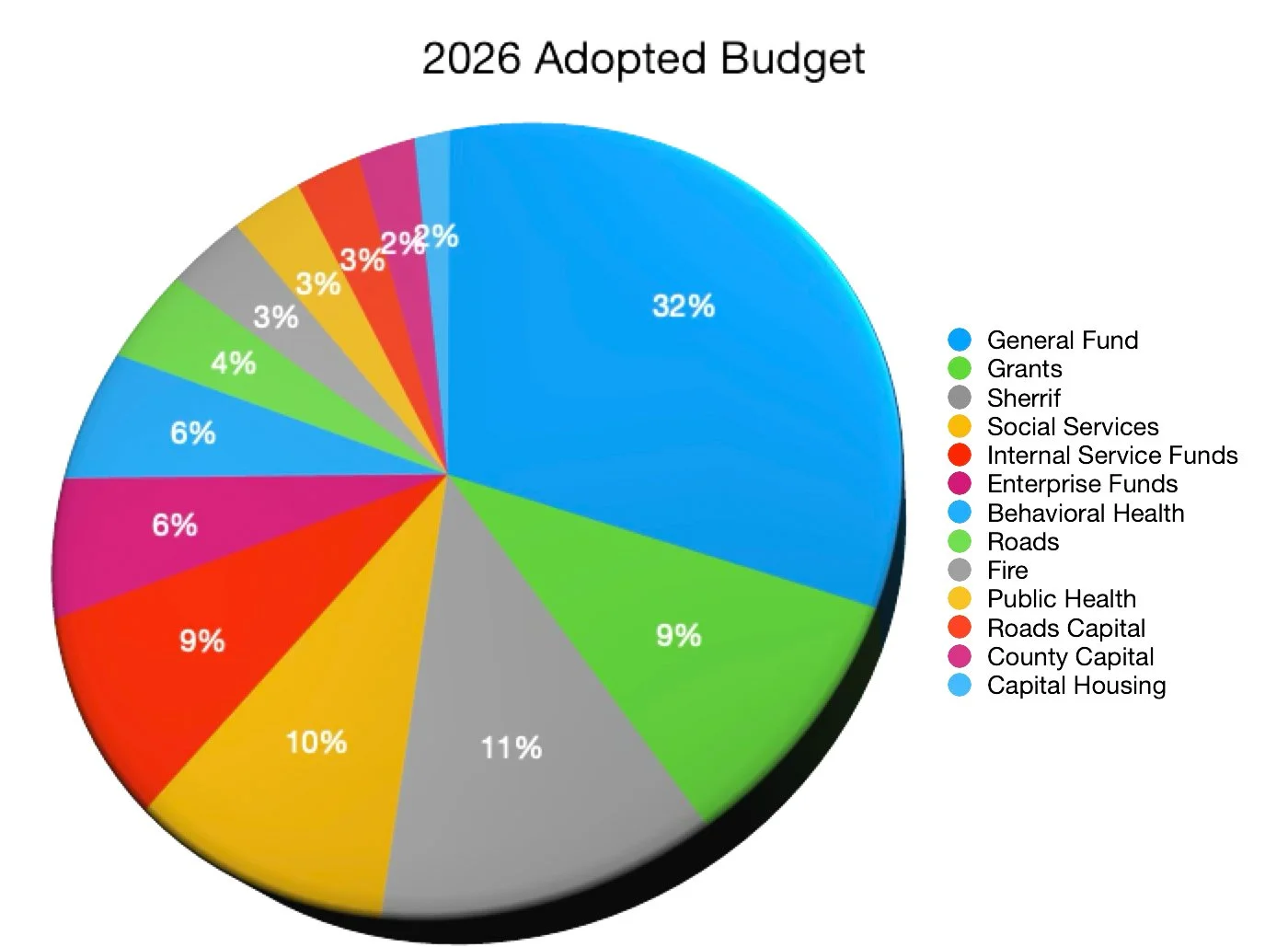

One reason debates like the one over Station 56 become so polarized is that most people understandably assume that counties have broad discretion over their finances. In reality, that discretion is limited.

A county budget is made up of multiple categories of funds, many of which are legally restricted to specific purposes. Only a portion of the budget, typically the General Fund, is truly flexible.

When people ask why the county cannot simply reallocate money from one area to another, the answer is often that it is legally prohibited from doing so. Contingency funds, however, are an exception. They exist precisely to provide flexibility when rigid funding structures collide with unpredictable realities. That is why the Station 56 decision resonated so strongly: it appeared to bypass one of the very tools designed to prevent this kind of outcome.

The Hidden Cost of Short-Term Thinking

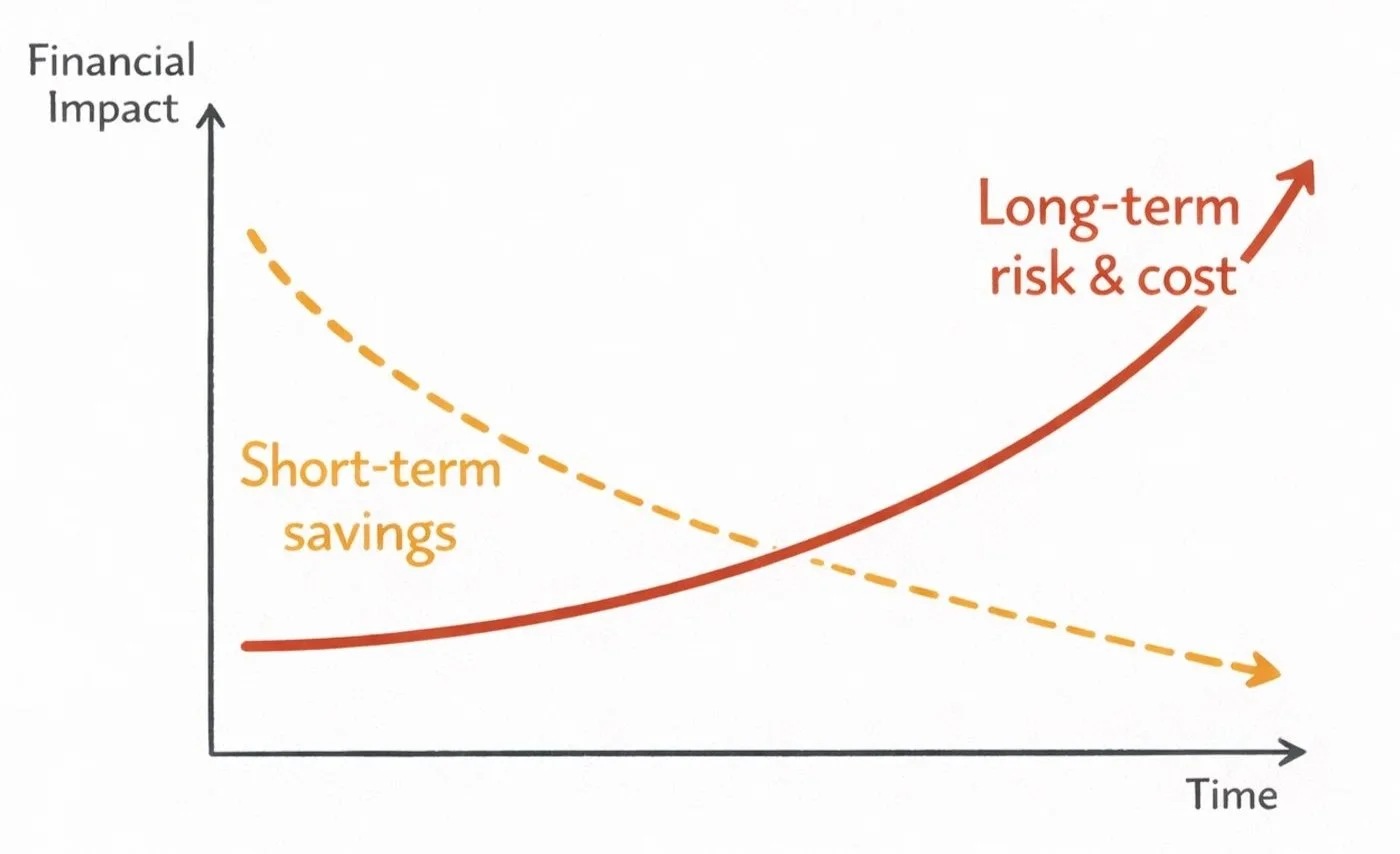

The consequences of defunding a fire station extend far beyond a single line item in a budget document. Longer response times, increased wildfire risk, pressure on insurance markets, and erosion of public trust are all part of the ripple effect. Paradoxically, what appears to be fiscal responsibility in the short term can become fiscal irresponsibility in the long term, as the costs of disasters and insurance crises dwarf the savings achieved by cutting preventative infrastructure.

Preventive spending is rarely politically convenient because it requires leaders to justify costs that avert disasters people cannot easily see. Yet history shows that investing in resilience is almost always cheaper than paying for catastrophe. Choosing to absorb short-term uncertainty in order to preserve long-term safety is not reckless; it is the essence of responsible governance.

A Question of Leadership and Priorities

The debate over Station 56 ultimately raises a deeper question about how Tuolumne County understands its role. Is the county primarily a financial entity tasked with balancing spreadsheets, or is it a living system responsible for safeguarding communities, infrastructure, and public trust?

Counties are not corporations, startups, or investment portfolios.

They are the backbone of everyday life. When they falter, the consequences are not measured in lost profits but in diminished safety and stability. The decision to defund Station 56 should not be remembered merely as a budgetary adjustment but as a moment that exposed the tension between fiscal caution and public responsibility.

Toward a More Resilient Approach

Tuolumne County does not need reckless spending, nor does it need reflexive austerity. What it needs is a more nuanced framework for decision-making, one that recognizes the difference between optional programs and essential infrastructure, between temporary uncertainty and permanent risk, and between financial prudence and false economy.

Using contingency funds strategically, planning for the inherent delays of grant funding, and treating public safety as foundational rather than discretionary are not radical ideas. They are the basic principles of resilient governance. The controversy surrounding Station 56 should serve as an opportunity to rethink how the county balances caution with courage and efficiency with responsibility.

The issue is not whether Tuolumne County can afford to invest in fire protection. The more difficult and important question is whether we can afford not to.